A 2012 data breach that was thought to have exposed 6.5 million hashed passwords for LinkedIn users instead likely impacted more than 117 million accounts, the company now says. In response, the business networking giant said today that it would once again force a password reset for individual users thought to be impacted in the expanded breach.

The 2012 breach was first exposed when a hacker posted a list of some 6.5 million unique passwords to a popular forum where members volunteer or can be hired to hack complex passwords. Forum members managed to crack some the passwords, and eventually noticed that an inordinate number of the passwords they were able to crack contained some variation of “linkedin” in them.

The 2012 breach was first exposed when a hacker posted a list of some 6.5 million unique passwords to a popular forum where members volunteer or can be hired to hack complex passwords. Forum members managed to crack some the passwords, and eventually noticed that an inordinate number of the passwords they were able to crack contained some variation of “linkedin” in them.

LinkedIn responded by forcing a password reset on all 6.5 million of the impacted accounts, but it stopped there. But earlier today, reports surfaced about a sales thread on an online cybercrime bazaar in which the seller offered to sell 117 million records stolen in the 2012 breach. In addition, the paid hacked data search engine LeakedSource claims to have a searchable copy of the 117 million record database (this service said it found my LinkedIn email address in the data cache, but it asked me to pay $4.00 for a one-day trial membership in order to view the data; I declined).

Inexplicably, LinkedIn’s response to the most recent breach is to repeat the mistake it made with original breach, by once again forcing a password reset for only a subset of its users.

“Yesterday, we became aware of an additional set of data that had just been released that claims to be email and hashed password combinations of more than 100 million LinkedIn members from that same theft in 2012,” wrote Cory Scott, in a post on the company’s blog. “We are taking immediate steps to invalidate the passwords of the accounts impacted, and we will contact those members to reset their passwords. We have no indication that this is as a result of a new security breach.”

LinkedIn spokesman Hani Durzy said the company has obtained a copy of the 117 million record database, and that LinkedIn believes it to be real.

“We believe it is from the 2012 breach,” Durzy said in an email to KrebsOnSecurity. “How many of those 117m are active and current is still being investigated.”

Regarding the decision not to force a password reset across the board back in 2012, Durzy said “We did at the time what we thought was in the best interest of our member base as a whole, trying to balance security for those with passwords that were compromised while not disrupting the LinkedIn experience for those who didn’t appear impacted.”

The 117 million figure makes sense: LinkedIn says it has more than 400 million users, but reports suggest only about 25 percent of those accounts are used monthly.

Alex Holden, co-founder of security consultancy Hold Security, was among the first to discover the original cache of 6.5 million back in 2012 — shortly after it was posted to the password cracking forum InsidePro. Holden said the 6.5 million encrypted passwords were all unique, and did not include any passwords that were simple to crack with rudimentary tools or resources [full disclosure: Holden’s site lists this author as an adviser, however I receive no compensation for that role].

“These were just the ones that the guy who posted it couldn’t crack,” Holden said. “I always thought that the hacker simply didn’t post to the forum all of the easy passwords that he could crack himself.”

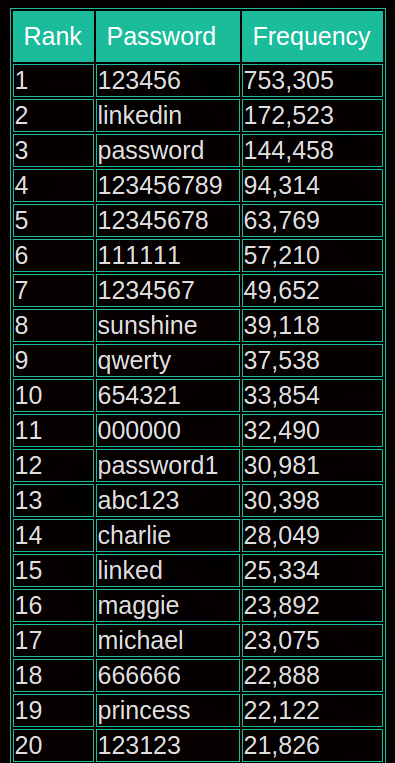

The top 20 most commonly used LinkedIn account passwords, according to LeakedSource.

According to LeakedSource, just 50 easily guessed passwords made up more than 2.2 million of the 117 million encrypted passwords exposed in the breach.

“Passwords were stored in SHA1 with no salting,” the password-selling site claims. “This is not what internet standards propose. Only 117m accounts have passwords and we suspect the remaining users registered using FaceBook or some similarity.”

SHA1 is one of several different methods for “hashing” — that is, obfuscating and storing — plain text passwords. Passwords are “hashed” by taking the plain text password and running it against a theoretically one-way mathematical algorithm that turns the user’s password into a string of gibberish numbers and letters that is supposed to be challenging to reverse.

The weakness of this approach is that hashes by themselves are static, meaning that the password “123456,” for example, will always compute to the same password hash. To make matters worse, there are plenty of tools capable of very rapidly mapping these hashes to common dictionary words, names and phrases, which essentially negates the effectiveness of hashing. These days, computer hardware has gotten so cheap that attackers can easily and very cheaply build machines capable of computing tens of millions of possible password hashes per second for each corresponding username or email address.

But by adding a unique element, or “salt,” to each user password, database administrators can massively complicate things for attackers who may have stolen the user database and rely upon automated tools to crack user passwords.

LinkedIn said it added salt to its password hashing function following the 2012 breach. But if you’re a LinkedIn user and haven’t changed your LinkedIn password since 2012, your password may not be protected with the added salting capabilities. At least, that’s my reading of the situation from LinkedIn’s 2012 post about the breach.

If you haven’t changed your LinkedIn password in a while, that would probably be a good idea. Most importantly, if you use your LinkedIn password at other sites, change those passwords to unique passwords. As this breach reminds us, re-using passwords at multiple sites that hold personal and/or financial information about you is a less-than-stellar idea.

Source: Krebs