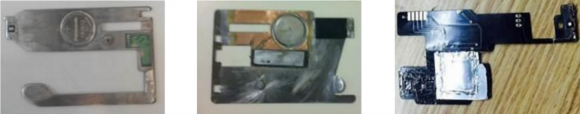

ATM maker NCR Corp. says it is seeing a rapid rise in reports of what it calls “deep insert skimmers,” wafer-thin fraud devices made to be hidden inside of the card acceptance slot on a cash machine.

KrebsOnSecurity’s All About Skimmers series has featured several stories about insert skimmers. But the ATM manufacturer said deep insert skimmers are different from typical insert skimmers because they are placed in various positions within the card reader transport, behind the shutter of a motorized card reader and completely hidden from the consumer at the front of the ATM.

NCR says these deep insert skimming devices — usually made of metal or PCB plastic — are unlikely to be affected by most active anti-skimming jamming solutions, and they are unlikely to be detected by most fraudulent device detection solutions.

“Neither NCR Skimming Protection Solution, nor other anti-skimming devices can prevent skimming with these deep insert skimmers,” NCR wrote in an alert sent to banks and other customers. “This is due to the fact the skimmer sits well inside the card reader, away from the detectors or jammers of [NCR’s skimming protection solution].

The company said it has received reports of these skimming devices on all ATM manufacturers in Greece, Ireland, Italy, Switzerland, Sweden, Bulgaria, Turkey, United Kingdom and the United States.

“This suggests that ‘deep insert skimming’ is becoming more viable for criminals as a tactic to avoid bezel mounted anti-skimming devices,” NCR wrote. The company said it is currently testing a firmware update for NCR machines that should help detect the insertion of deep insert skimmers and send an alert.

A DEEP DIVE ON DEEP INSERT SKIMMERS

Charlie Harrow, solutions manager for global security at NCR, said the early model insert skimmers used a rudimentary wireless transmitter to send card data. But those skimmers were all powered by tiny coin batteries like the kind found in watches, and that dramatically limits the amount of time that the skimmer can transmit card data.

Harrow said NCR suspects that the deep insert skimmer makers are using tiny pinhole cameras hidden above or beside the PIN pad to record customers entering their PINs, and that the hidden camera doubles as a receiver for the stolen card data sent by the skimmer nestled inside the ATM’s card slot. He suspects this because NCR has never actually found a hidden camera along with an insert skimmer. Also, a watch-battery run wireless transmitter wouldn’t last long if the signal had to travel very far.

According to Harrow, the early model insert skimmers weren’t really made to be retrieved. Turns out, that may have something to do with the way card readers work on ATMs.

“Usually what happens is the insert skimmer causes a card jam,” at which point the thief calls it quits and retrieves his hidden camera — which has both the card data transmitted from the skimmer and video snippets of unwitting customers entering their PINs, he said. “These skimming devices can usually cope with most cards, but it’s just a matter of time before a customer sticks an ATM card in the machine that is in less-that-perfect condition.”

The latest model deep insert skimmers, Harrow said, include a tiny memory chip that can hold account data skimmed off the cards. Presumably this is preferable to sending the data wirelessly because writing the card data to a memory chip doesn’t drain as much power from the wimpy coin battery that powers the devices.

The deep insert skimmers also are designed to be retrievable:

“The ones I’ve seen will snap into some of the features inside the card reader, which has got various nooks and crannies,” Harrow said. “The latest ones also have magnets in them which are used to hold them down against the card reader.” Harrow says the magnets are on the opposite side of the device from the card reader, so the magnets don’t interfere with the skimmer’s job of reading the data off of the card’s magnetic stripe.

Many readers have asked why the fraudsters would bother skimming cards from ATMs in Europe, which long ago were equipped to read data off the chip embedded in the cards issued by European banks. The trouble is that virtually all chip cards still have the account data encoded in plain text on the magnetic stripe on the back of the card — mainly so that the cards can be used in ATM locations that cannot yet read chip-based cards (i.e., the United States).

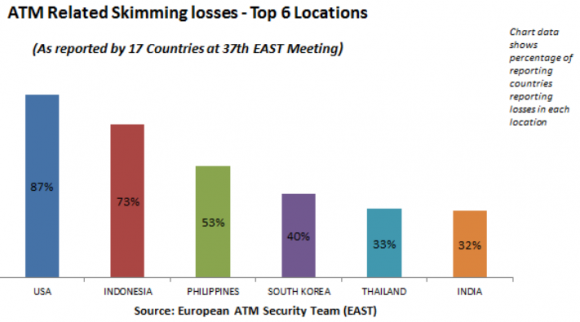

When thieves skim data from ATMs in Europe, they generally sell the data to fraudsters who will encode the card data onto counterfeit cards and withdraw cash at ATMs in the United States or in other countries that haven’t yet fully moved to chip-based cards. In response, some European financial institutions have taken to enacting an anti-fraud mechanism called “geo-blocking,” which prevents the cards from being used in certain areas.

“Where geo-blocking has been widely or partially implemented, the international loss profile is very different, with minimal losses reported,” wrote the European ATM Security Team (EAST) in their latest roundup of ATM skimming attacks in 2015 (for more on that, see this story). “From the perspective of European card issuers the USA and the Asia-Pacific region are where the majority of such losses are being reported.”

Even after most U.S. banks put in place chip-capable ATMs, the magnetic stripe will still be needed because it’s an integral part of the way ATMs work: Most ATMs in use today require a magnetic stripe for the card to be accepted into the machine. The principal reason for this is to ensure that customers are putting the card into the slot correctly, as embossed letters and numbers running across odd spots in the card reader can take their toll on the machines over time.

Source: Krebs