The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) this week warned about a “dramatic” increase in so-called “CEO fraud,” e-mail scams in which the attacker spoofs a message from the boss and tricks someone at the organization into wiring funds to the fraudsters. The FBI estimates these scams have cost organizations more than $2.3 billion in losses over the past three years.

In an alert posted to its site, the FBI said that since January 2015, the agency has seen a 270 percent increase in identified victims and exposed losses from CEO scams. The alert noted that law enforcement globally has received complaints from victims in every U.S. state, and in at least 79 countries.

CEO fraud usually begins with the thieves either phishing an executive and gaining access to that individual’s inbox, or emailing employees from a look-alike domain name that is one or two letters off from the target company’s true domain name. For example, if the target company’s domain was “example.com” the thieves might register “examp1e.com” (substituting the letter “L” for the numeral 1) or “example.co,” and send messages from that domain.

Unlike traditional phishing scams, spoofed emails used in CEO fraud schemes rarely set off spam traps because these are targeted phishing scams that are not mass e-mailed. Also, the crooks behind them take the time to understand the target organization’s relationships, activities, interests and travel and/or purchasing plans.

They do this by scraping employee email addresses and other information from the target’s Web site to help make the missives more convincing. In the case where executives or employees have their inboxes compromised by the thieves, the crooks will scour the victim’s email correspondence for certain words that might reveal whether the company routinely deals with wire transfers — searching for messages with key words like “invoice,” “deposit” and “president.”

On the surface, business email compromise scams may seem unsophisticated relative to moneymaking schemes that involve complex malicious software, such as Dyre and ZeuS. But in many ways, CEO fraud is more versatile and adept at sidestepping basic security strategies used by banks and their customers to minimize risks associated with account takeovers. In traditional phishing scams, the attackers interact with the victim’s bank directly, but in the CEO scam the crooks trick the victim into doing that for them.

The FBI estimates that organizations victimized by CEO fraud attacks lose on average between $25,000 and $75,000. But some CEO fraud incidents over the past year have cost victim companies millions — if not tens of millions — of dollars.

Last month, the Associated Press wrote that toy maker Mattel lost $3 million in 2015 thanks to a CEO fraud phishing scam. In 2015, tech firm Ubiquiti disclosed in a quarterly financial report that it suffered a whopping $46.7 million hit because of a CEO fraud scam. In February 2015, email con artists made off with $17.2 million from The Scoular Co., an employee-owned commodities trader. More recently, I wrote about a slightly more complex CEO fraud scheme that incorporated a phony phone call from a phisher posing as an accountant at KPMG.

The FBI urges businesses to adopt two-step or two-factor authentication for email, where available, and to establish other communication channels — such as telephone calls — to verify significant transactions. Businesses are also advised to exercise restraint when publishing information about employee activities on their Web sites or through social media, as attackers perpetrating these schemes often will try to discover information about when executives at the targeted organization will be traveling or otherwise out of the office.

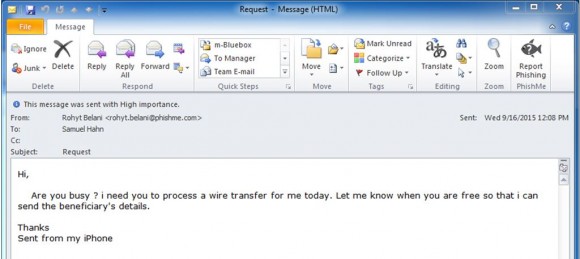

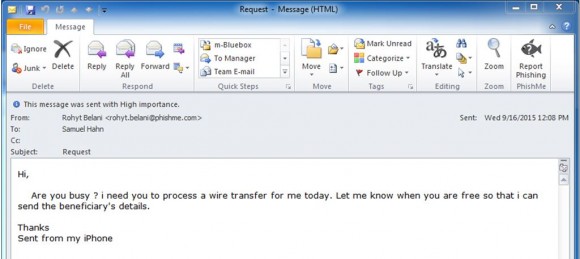

For an example of what some of these CEO fraud scams look like, check out this post from security education and awareness firm Phishme about scam artists trying to target the company’s leadership.

I’m always amazed when I hear security professionals I know and respect make comments suggesting that phishing and spam are solved problems. The right mix of blacklisting and email validation regimes like DKIM and SPF can block the vast majority of this junk, these experts argue.

But CEO fraud attacks succeed because they rely almost entirely on tricking employees into ignoring or sidestepping some very basic security precautions. Educating employees so that they are less likely to fall for these scams won’t block all social engineering attacks, but it should help. Remember, the attackers are constantly testing users’ security awareness. Organizations might as well be doing the same, using periodic tests to identify problematic users and to place additional security controls on those individuals.

Source: Krebs