Spammers are abusing ill-configured U.S. dot-gov domains and link shorteners to promote spammy sites that are hidden behind short links ending in”usa.gov”.

Spam purveyors are taking advantage of so-called “open redirects” on several U.S. state Web sites to hide the true destination to which users will be taken if they click the link. Open redirects are potentially dangerous because they let spammers abuse the reputation of the site hosting the redirect to get users to visit malicious or spammy sites without realizing it.

Spam purveyors are taking advantage of so-called “open redirects” on several U.S. state Web sites to hide the true destination to which users will be taken if they click the link. Open redirects are potentially dangerous because they let spammers abuse the reputation of the site hosting the redirect to get users to visit malicious or spammy sites without realizing it.

For example, South Dakota has an open redirect:

http://dss.sd.gov/scripts/programredirect.asp?url=

…which spammers are abusing to insert the name of their site at the end of the script. Here’ a link that uses this redirect to route you through dss.sd.gov and then on to krebsonsecurity.com. But this same redirect could just as easily be altered to divert anyone clicking the link to a booby-trapped Web site that tries to foist malware.

The federal government’s stamp of approval comes into the picture when spammers take those open redirect links and use bit.ly to shorten them. Bit.ly’s service automatically shortens any US dot-gov or dot-mil (military) site with a “1.usa.gov” shortlink. That allows me to convert the redirect link to krebsonsecurity.com from the ungainly….

http://dss.sd.gov/scripts/programredirect.asp?url=http://krebsonsecurity.com

…into the far less ugly and perhaps even official-looking:

http://1.usa.gov/1pwtneQ.

Helpfully, Uncle Sam makes available a list of all the 1.usa.gov links being clicked at this page. Keep an eye on that and you’re bound to see spammy links going by, as in this screen shot. One of the more recent examples I saw was this link — http:// 1.usa[dot]gov/1P8HfQJ# (please don’t visit this unless you know what you’re doing) — which was advertised via Skype instant message spam, and takes clickers to a fake TMZ story allegedly about “Gwen Stefani Sharing Blake Shelton’s Secret to Rapid Weight Loss.”

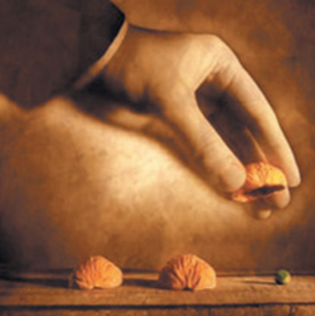

Spammers are using open redirects on state sites and bit.ly to make spammy domains like this one look like .gov links.

Unfortunately, a minute or so of research online shows that exact issue was highlighted almost four years ago by researchers at Symantec. In October 2012, Symantec said it found that about 15 percent of all 1.usa.gov URLS were used to promote spammy messages. I’d be curious to know the current ratio, but I doubt it has changed much.

A story at the time about the Symantec research in Sophos‘s Naked Security blog noted that the curator of usa.gov — the U.S. General Services Administration’s Office of Citizen Services and Innovative Technology — was working with bit.ly to filter out malicious or spammy links — pointing to a interstitial warning that bit.ly pops up when it detects a suspicious link is being shortened.

KrebsOnSecurity requested comment from both bit.ly and the GSA, and will update this post in the event that they respond.

I wanted to get a sense of how well bit.ly’s system would block any .gov redirects that sent users to known malicious Web sites. So I created .gov shortlinks using the South Dakota redirect, bit.ly, and the first page of URLs listed at malwaredomainlist.com — a site that tracks malicious links being used in active attacks.

The result? Bit.ly’s system allowed clicks on all of the shortened malicious links that didn’t end in “.exe,” which was most of them. It’s nice that bit.ly at least tries to filter out malicious links, but perhaps the better solution is for U.S. state and federal government sites to get rid of open redirects altogether.

I generally don’t trust shortened links, and have long relied on the Unshorten.it extension for Google Chrome, which lets users unshorten any link by right clicking on it and selecting “unshorten this link”. Unshorten.it also pulls reputation data on each URL from Web of Trust (WOT).

Fun fact: Adding a “+” to the end of any link shortened with bit.ly will take you to a page on bit.ly that displays the link actual link that was shortened.

How do you respond to shortened links? Sound off in the comments below.

Source: Krebs